In traditional wood framing, if you want to move a window, you grab a hammer and shift a stud. In a pre-engineered metal building, that same "simple" change might require recalculating the wind load for the entire structure—and could cost you $5,000 or more.

At Indaco Metals, we've been manufacturing steel buildings in Oklahoma since 1995. In that time, we've seen a few projects where a small customer oversight during planning turned into a major expense during construction. We call this the "Domino Effect," and understanding it is the key to keeping your metal building project on time and on budget.

The most expensive mistake customers make is treating a steel building kit like a pile of lumber. With wood framing, there's built-in redundancy—studs are placed every 16 inches, and if one is compromised, the load shifts to its neighbors. You can improvise.

Pre-engineered metal buildings work differently. Every column, purlin, and girt is calculated to perform a specific function under exact load conditions. There's no excess material, no buffer, and no room for improvisation.

Think of it this way: a wood-framed structure is like a net, where the load spreads across many connection points. A steel building is more like a bridge, where massive "red iron" frames spaced 20 to 25 feet apart carry concentrated loads along precisely calculated paths. When you modify one component, you're not making a local change—you're potentially affecting the entire structural system.

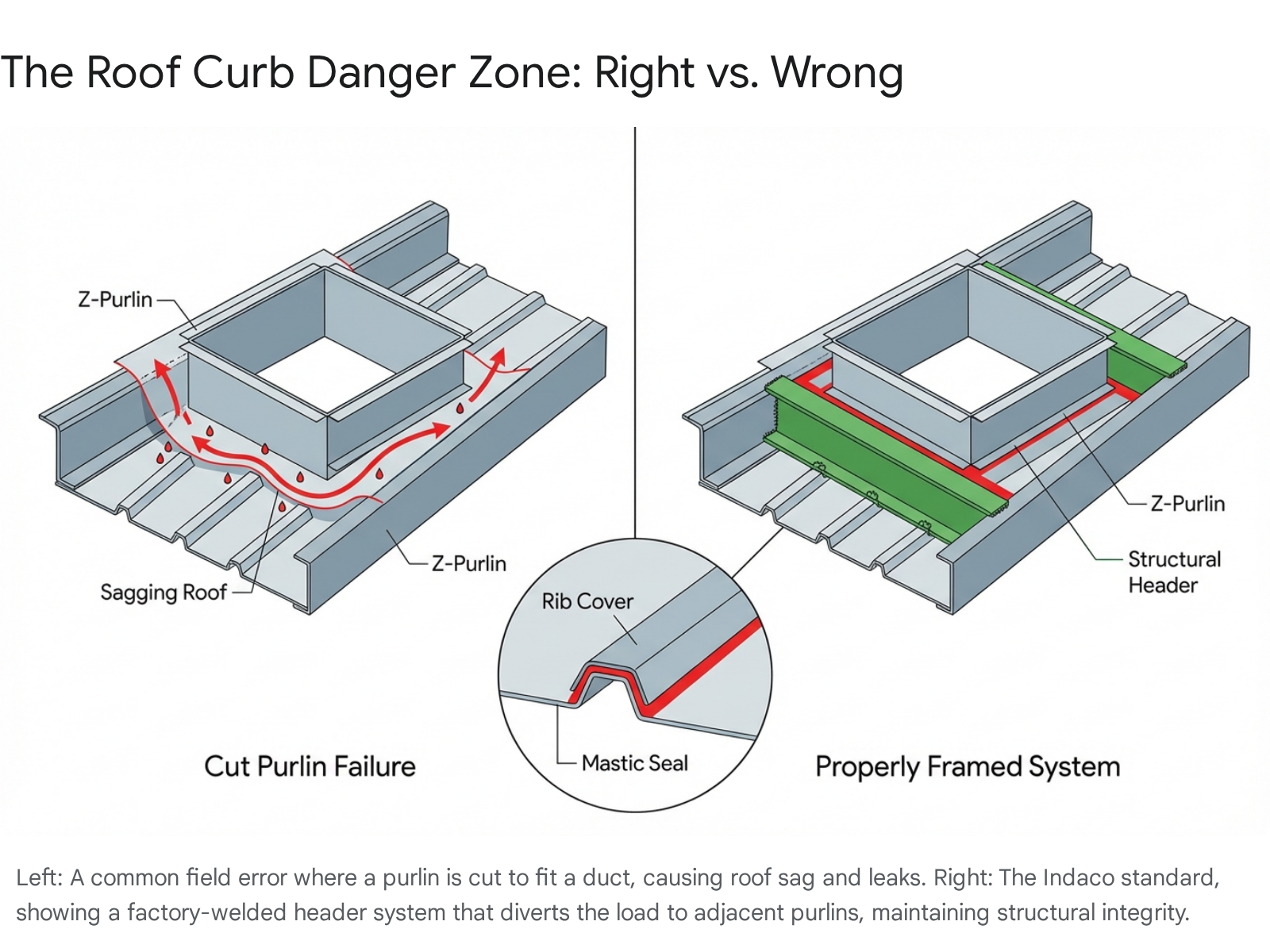

One of the most common triggers of the Domino Effect is adding HVAC equipment to the roof after the building is designed. In our experience, improperly installed roof-mounted AC units are among the leading causes of leaks in Oklahoma metal buildings.

When HVAC placement is decided before engineering, we can integrate mechanical needs into the structural design. We add sub-framing—essentially a steel "bridge"—under the roof to support the weight of the unit. The opening is factory-framed with headers and trimmers that transfer loads safely to adjacent purlins. Rib covers and mastic seals are matched precisely to your roof panel profile.

When you decide to add a 5-ton AC unit after the kit arrives, problems multiply. An HVAC contractor—often more accustomed to wood decks—places the unit where it's convenient for ductwork and cuts a hole in the roof.

The consequences can be severe. If the cut intersects a purlin (the horizontal beams that support your roof panels), that structural member no longer carries its designed load. The roof panels sag, creating a depression where water pools. Without factory-welded curbs, you're relying on field flashing that rarely seals properly against Oklahoma's temperature swings and driving rain.

Left: A common field error where a purlin is cut to fit a duct, causing roof sag and leaks. Right: The Indaco standard, showing a factory-welded header system that diverts the load to adjacent purlins, maintaining structural integrity.

The repair cost for a roof cut through a purlin typically runs $2,000 to $5,000—plus the ongoing maintenance headaches of a leak-prone roof.

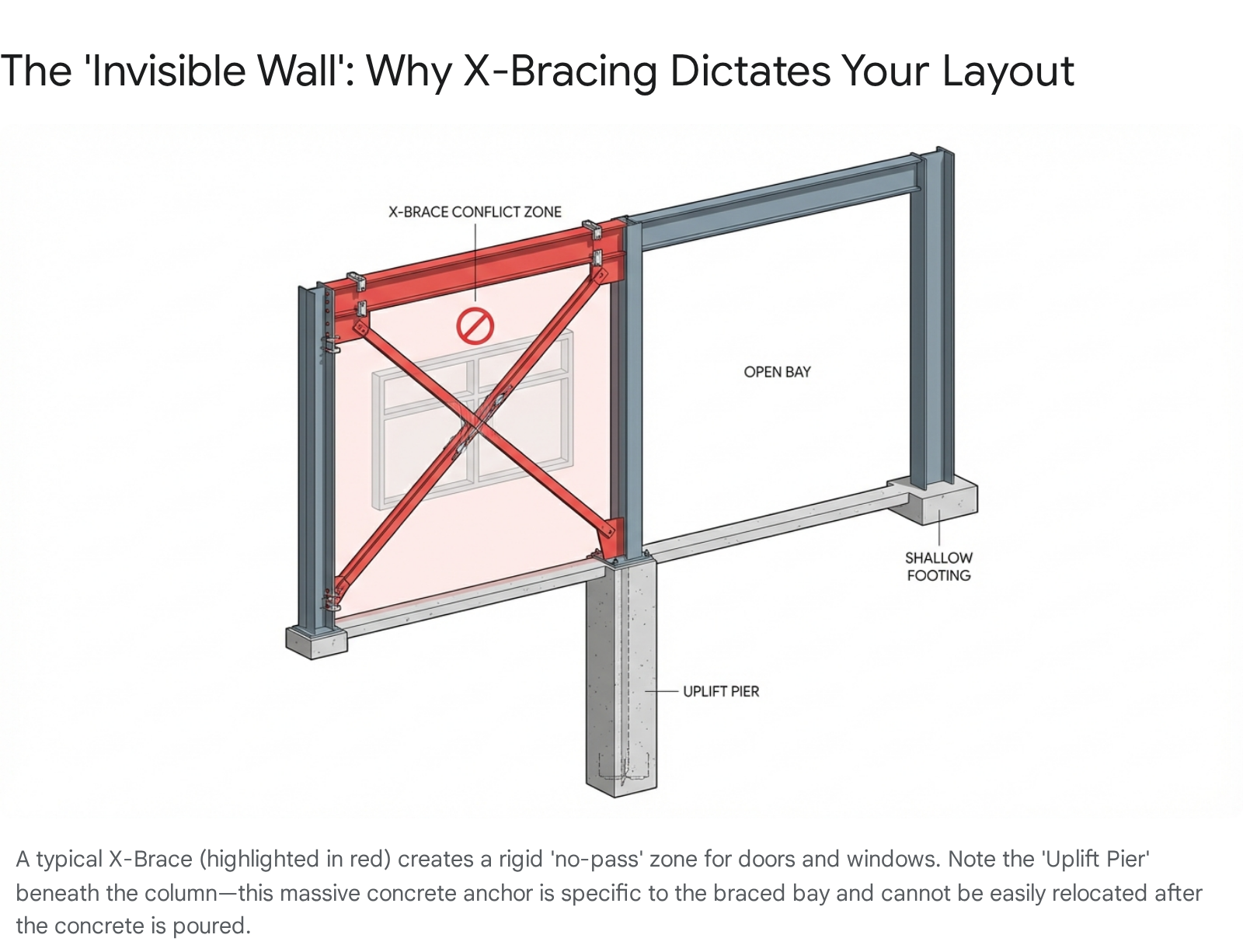

Perhaps the most frustrating Domino Effect scenario involves the collision between what customers want (doors, windows, open wall space) and what the structure needs (X-bracing).

X-bracing consists of steel cables or rods that form a large "X" between columns, providing the lateral stability that keeps your building from racking—leaning over like a cardboard box with open ends. To the building owner, a wall looks like a blank canvas. To the structural engineer, certain walls are designated "braced bays" that cannot be modified.

Picture this: A customer orders a 40x60 shop and approves drawings showing X-bracing in the center sidewall bay. The steel arrives. During erection, they stand in the framed shell and decide a roll-up door would be perfect—right where the X-brace is located.

"Just move the brace to the next bay," they say.

Here's what actually happens:

The columns in the new bay don't have the welded connection clips needed to accept the brace. Field welding damages the protective coating and voids the warranty. The adjacent columns may be lighter-duty, designed only for gravity loads rather than the tension and compression forces of bracing. Most critically, the foundation pier under the original braced column was designed to resist "uplift"—the wind trying to pull the building out of the ground. The pier under the adjacent column is a standard compression footing that could literally be pulled from the concrete.

A typical X-Brace (highlighted in red) creates a rigid “no-pass” zone for doors and windows. Note the “Uplift Pier” beneath the column. This massive concrete anchor is specific to the braced bay and cannot be easily relocated after the concrete is poured.

The cost to move that door 20 feet? Potentially $5,000 to $10,000, plus a 4-6 week delay for re-engineering and fabrication.

If you need openings in every bay—like a fire station with multiple garage doors—we can design the building with portal frames instead of X-bracing. Portal frames are heavier built-up frames that provide stability without cables. They cost more than X-bracing and require larger columns, but this decision must be made during the sales process, not during erection.

Oklahoma presents a unique geological challenge that acts as the first domino in many failed projects: Permian Red Clay. This soil swells significantly when wet and shrinks dramatically when dry. In some areas, the ground can heave several inches seasonally, cracking standard concrete slabs.

Many builders pour a standard 4-inch slab, thinking "concrete is concrete." But a steel building concentrates enormous point loads at each column—often 20,000 to 50,000 pounds at a single location. A standard residential slab will punch through under that pressure.

Additionally, Oklahoma's 115 mph wind requirements mean your foundation must resist uplift forces trying to pull the building out of the ground. A slab-on-grade without properly engineered piers or thickened edges will crack and lift.

Here's a scenario we see too often: A customer orders a building, then gets their soil test. The geotechnical report reveals poor bearing capacity—1,500 psf instead of the assumed 3,000 psf. Now we may need to redesign the column base plates.

If the steel is already fabricated for a "pinned base" design (larger footings, lighter columns), but the soil dictates a "fixed base" design (smaller footings, heavier columns), the fabricated steel may be unusable.

Our recommendation: Always perform a soil test before final engineering. This allows us to optimize the design for your specific site conditions, potentially saving thousands in concrete costs while ensuring your building performs as intended.

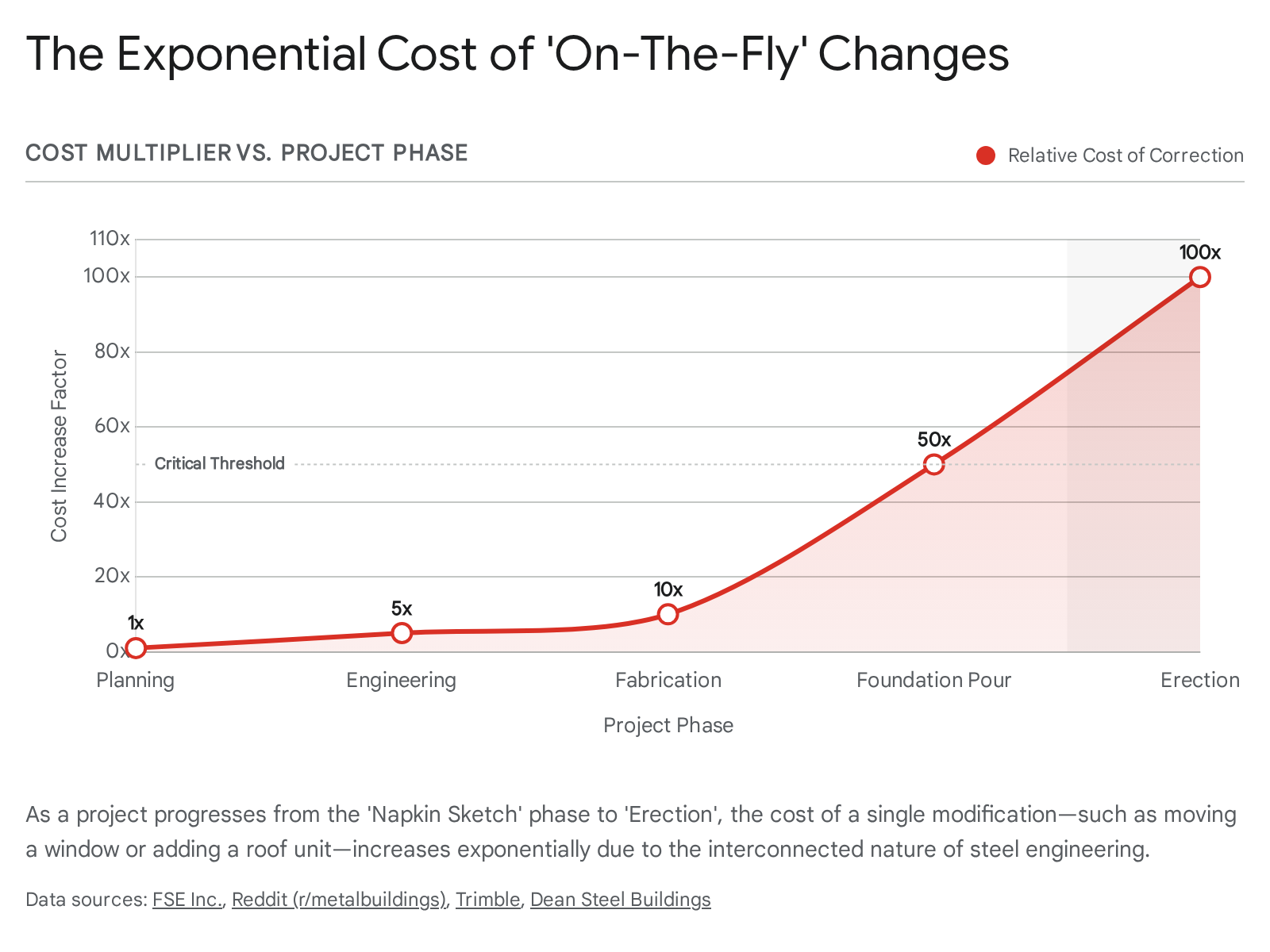

The financial impact of the Domino Effect follows an exponential curve:

A modification that costs nothing during the planning phase can easily balloon to $10,000 or more during erection. The steel is cut, the crews are mobilized, and every day of delay adds cost.

To help you avoid the Domino Effect, we recommend finalizing these details before your building goes to engineering:

Will your units be ground-mounted or roof-mounted? Ground units eliminate roof penetrations entirely. Roof units require engineered curbs—we need exact make, model, and weight specifications. Have you planned for adequate eave height if you need ceiling-mounted heaters or fans?

Have you mapped every door location against the structural layout? Know the exact model of your overhead doors—a "12-foot door" might need 14 feet of clearance for high-lift tracks. Check that door tracks won't interfere with planned lighting or HVAC equipment.

Have you verified window locations don't conflict with X-bracing? Consider future needs—it's much cheaper to frame an opening now and panel over it than to cut one later.

Do you plan to add liner panels (interior metal walls)? We need to include framing to attach them. Will you need electrical conduit pass-throughs in the rigid frames? Factory-punched holes cost a fraction of field drilling through half-inch steel.

If you're installing a vehicle lift, we need clear height requirements, not just eave height. Heavy equipment like cranes or hoists require reinforced framing designed from the start.

Do you anticipate adding square footage later? Expandable endwall framing can be designed now at minimal cost, saving substantial expense when you're ready to grow.

Building in Oklahoma means accounting for our unique climate challenges:

Modern building codes require 115 mph 3-second gust ratings—not the older 90 mph "fastest mile" standard. If you're comparing quotes, make sure everyone is engineering to the same standard. A building designed to outdated specs will not pass inspection in counties like Oklahoma, Tulsa, or Cleveland.

A building designed as "Agricultural Use" (Risk Category I) cannot legally be converted to a shop with employees (Risk Category II) or living space without potentially replacing the main frames. Always design for the highest probable future use.

At Indaco Metals, we don't just sell steel—we help you plan a building system designed to weather Oklahoma's elements for generations. By partnering with us early in the planning phase, before the concrete is poured and permits are filed, you ensure the only thing your building accumulates is value, not change orders.

Our team has been manufacturing metal buildings right here in Oklahoma since 1995. We understand local soil conditions, wind requirements, and building codes. We're here to ask the questions that save you money—not to be annoying, but to protect your investment.

Don't let the first domino fall. Contact Indaco Metals today to start your planning session with our experienced team.

Visit our showrooms:

Shawnee: 3 American Way, Shawnee, OK 74804

(405) 273-9200

Sand Springs: 17427 W 9th St, Sand Springs, OK 74063

(918) 419-6053

Online: Request a quote | Try our 3D Builder

Complete this short form, or give us a call anytime: